While he was staying in Northfield in the summer of 1885, a Princeton College student and YMCA member named Luther Wishard found himself at Mount Hermon at the invitation of D.L. Moody. At that first meeting, Moody mentioned his idea of a gathering of YMCA secretaries at Mount Hermon the next summer. When the two crossed paths again less than a year later, Wishard proposed that college students should be invited to the gathering as well.

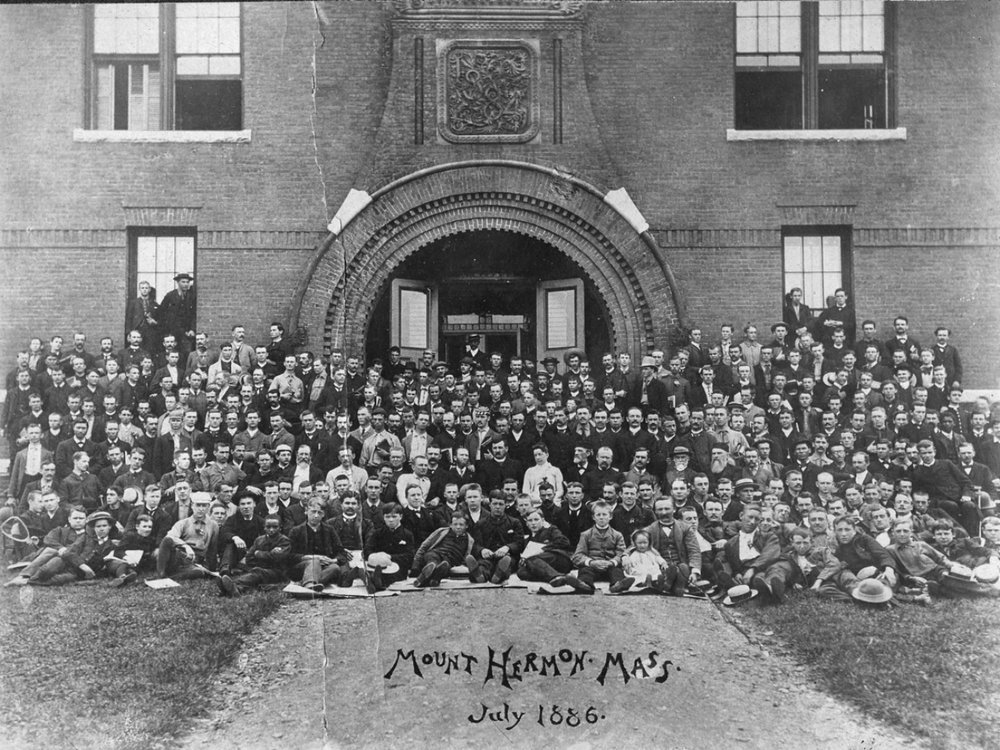

Their exchange gave birth to the Mount Hermon Bible Conference, held in 1886 from July 7 to August 2. A total of 251 students from 89 colleges and universities around the nation gathered for services led by Moody and heard teaching from ministers, missionaries, and seminary professors. Held in tranquil Northfield at the Mount Hermon Boys School, the conference offered a unique environment of fellowship, prayer, and Bible study for the students who converged there. In addition, for one recent graduate of Princeton named Robert Wilder, the gathering was an opportunity to spread an important message.

Wilder had been born to missionary parents in India, and his childhood had instilled in him a passion for foreign missions. The Mount Hermon Bible Conference was the perfect chance to share this passion with others in attendance. At first, Wilder began meeting with small groups of students for prayer meetings in the afternoons. Moody later permitted him to organize the Meeting of the Ten Nations, a special session where representatives of ten foreign countries spoke to the students of the need for missionaries in other parts of the world.

That meeting sparked great interest in foreign missions, demonstrated by the famous Mount Hermon One Hundred, a group of 100 students in attendance who pledged their intent to become foreign missionaries. Wilder sensed that the story of these willing volunteers had potential to inspire even more students if it could be spread. In the year following the conference, Wilder and another student named John Forman visited 162 colleges and universities with news of those first hundred volunteers, and soon over 2,000 students had pledged to become foreign missionaries.

From that point growth was exponential, and the group was formally organized in 1888 as the Student Volunteer Movement, or SVM. Thanks to dedicated student groups on college campuses and regular conventions held around the country, the SVM established itself as a leading recruiter of missionaries through the turn of the century. An estimated 20,000 students became foreign missionaries over the lifetime of the SVM, and tens of thousands more dedicated their support in other ways.

The student volunteers believed sincerely and fervently in the importance of the missionary cause. In his biography of D.L. Moody, J. Wilbur Chapman writes,

“It is said that the student attitude of many colleges . . . has completely changed, and certain it is that no other subject has ever taken such a deep hold on the convictions of college men, or has called forth from them such unselfish devotion.”[1]

Indeed, many men and women gave up previous ambitions in favor of becoming missionaries. The optimistic and determined spirit of the movement is captured in its motto: “The evangelization of the world in this generation.” It may well be an ambitious declaration, but in these resolute words one can hear echoes of the life of D.L. Moody, who remained fixed on his call to take the gospel of Jesus Christ wherever he went.

The student volunteers sparked a remarkable interest in missions among lay people as well, as Ben Harder notes:

“Many volunteers who did not get to the field infused the church with missionary-minded youth in positions of leadership.”[2]

And just as D.L. Moody transcended denominational boundaries with his evangelistic message, the growth of the SVM contributed to greater unity among believers across the globe. Speaking about the International Student Conferences organized by the SVM, Harder writes,

“This transatlantic interchange resulted in an affinity among volunteers all over the world, as well as the development of an appreciation for unity among churches in the missionary enterprise.”[3]

Many would point out that the SVM was far from perfect. Much of the spiritual fervor that characterized its founders dwindled as it grew into a worldwide organization and began to face pressure to sustain growth and produce results. No organization is immune to the danger of decay over time, and the SVM was no exception. While the group itself no longer exists, the resolve and sincerity of men like Wishard, Wilder, Moody, and others is preserved through the story of the original Mount Hermon Bible Conference. The fruit of the work of thousands of volunteers who dedicated themselves to serve as missionaries cannot be measured. At its core, the movement was and continues to be a reminder to believers everywhere of the call to spread the good news of Jesus Christ.

[1] Chapman, J. Wilbur. The Life and Work of Dwight. L. Moody. International Publishing Co., 1900

[2] Ben Harder, “The Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions and Its Contribution to 20th Century Missions,” Missiology, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2 April 1980.

[3] Ibid.